How to develop a game model? Part 1

1. The development of a game model in football

1.1 The importance and relevance of the game model in modern football

Football is a complex sport influenced by many factors, making it challenging to predict. To succeed, teams must master the multifaceted nature of the game through a comprehensive game model. Operating without such a model is akin to embarking on a road trip without a destination; it's essential for having a clear, conceptual understanding of the desired style of play. Moreover, a game model that focuses only on a few aspects will lack a holistic view of the game. Before discussing what constitutes a complete game model, we should first define it: A game model encapsulates a coach's vision for how the team should play.

The GAME model is how a coach wants the team to play soccer; a conception of the game. Given the high unpredictability that exists during a match, a coach tries to create predictability through preparation, planning and training . (DELGADO-BORDONAU & MÉNDEZ-VILLANUEVA, 2012, N.P)

We now understand that the game model represents the conceptual idea from the coaches, the club, etc., about how the team should play. However, simply knowing the definition of a game model doesn't teach us how to develop one for our own team.

To begin developing a game model, it is helpful to consider the following questions:

How can we create a game model that individually and collectively fits our team?

How can we ensure the game model encompasses all aspects of the game?

How can we formulate a game model that is easy for our players to understand?

The creation of a game model must incorporate the following considerations:

- Viewing the game itself as a model

- The game cycle

- The club’s philosophy

- The desired playing style and the coach’s beliefs

- The players' abilities and specific requirements for each position

- Dynamic evolution of the game model over time

- Adjustments based on opponents

- Environmental and cultural contexts

- The approach to development or success

1.2 The Game Itself as a Model

To create a game model derived from the game, we need to use the game itself as a model. This involves first developing a requirements model based on the game. In the illustration below, you can see the factors that are important to the game. In my model, I differentiate between six common factors, which include:

- Technical requirements of the game

- Tactical requirements of the game

- Physical/Athletical requirements of the game

- Psychological requirements of the game

- Sociological requirements of the game

- Cognitive requirements of the game

As you can see, we can mainly differentiate between five techniques in addition to ball mastery. Under "ball mastery," I understand the player's capacity to handle and feel the ball, which encompasses numerous techniques.

Within the tactical requirements of the game, we can basically differentiate among individual, group, and team tactics:

Individual tactics refer to 1 vs 1 scenarios, both offensive and defensive, and the overall individual tactical behavior in changing game situations, such as running free, showing for the ball, and positioning within space.

Group tactics encompass all kinds of numerical advantage and disadvantage situations plus equal number game formats, ranging from 2 vs 1 to 6 vs 6.

Team tactics refer to the entire team's strategy. Whether playing 11 vs 11 or smaller formats like 9 vs 9, 8 vs 8, or 7 vs 7, it always pertains to the actual number of players competing in the match.

The physical requirements of the game include Endurance, Speed, Strength, Agility, Flexibility, and Coordination. Each of these areas can be further divided into sub-areas. For example, the area of Coordination differentiates between seven coordinative abilities: balance, kinesthetic differentiation, reaction, orientation, combination of movements, conversion, and rhythm.

The game also places high demands on psychological aspects, such as dealing with stressful situations, handling success and setbacks, etc. Motivation and volition are also crucial, among many other factors.

The sociological factors of the game emphasize that football is played by a team of 11, working collectively. Each player must fulfill specific functional roles within the team. For a team to be successful, members must cooperate and interact positively with each other, making the relationships between teammates crucial.

Last but not least, my model includes cognitive factors. As the name suggests, this pertains to everything connected to how the brain perceives, selects, and processes information.

One of the most crucial messages of this chapter is that none of these areas can be viewed in isolation, as all of them are interconnected. A player lacking in good passing technique will struggle to execute specific tactical actions. Similarly, a player who lacks endurance may not maintain high-quality play over 90+ minutes. Furthermore, a player who is not a team player may fall short in executing collective tactical actions. There are numerous examples like these. Ultimately, it is essential to adopt a holistic view of the game, which should then inform a holistic training approach. I observe that many coaches focus on isolated parts of the game without linking them to other areas, resulting in a gap in their development approach.

In the next step, we will explore the game cycle, also often referred to as the four moments of the game.

1.2 The Game Itself as a Model

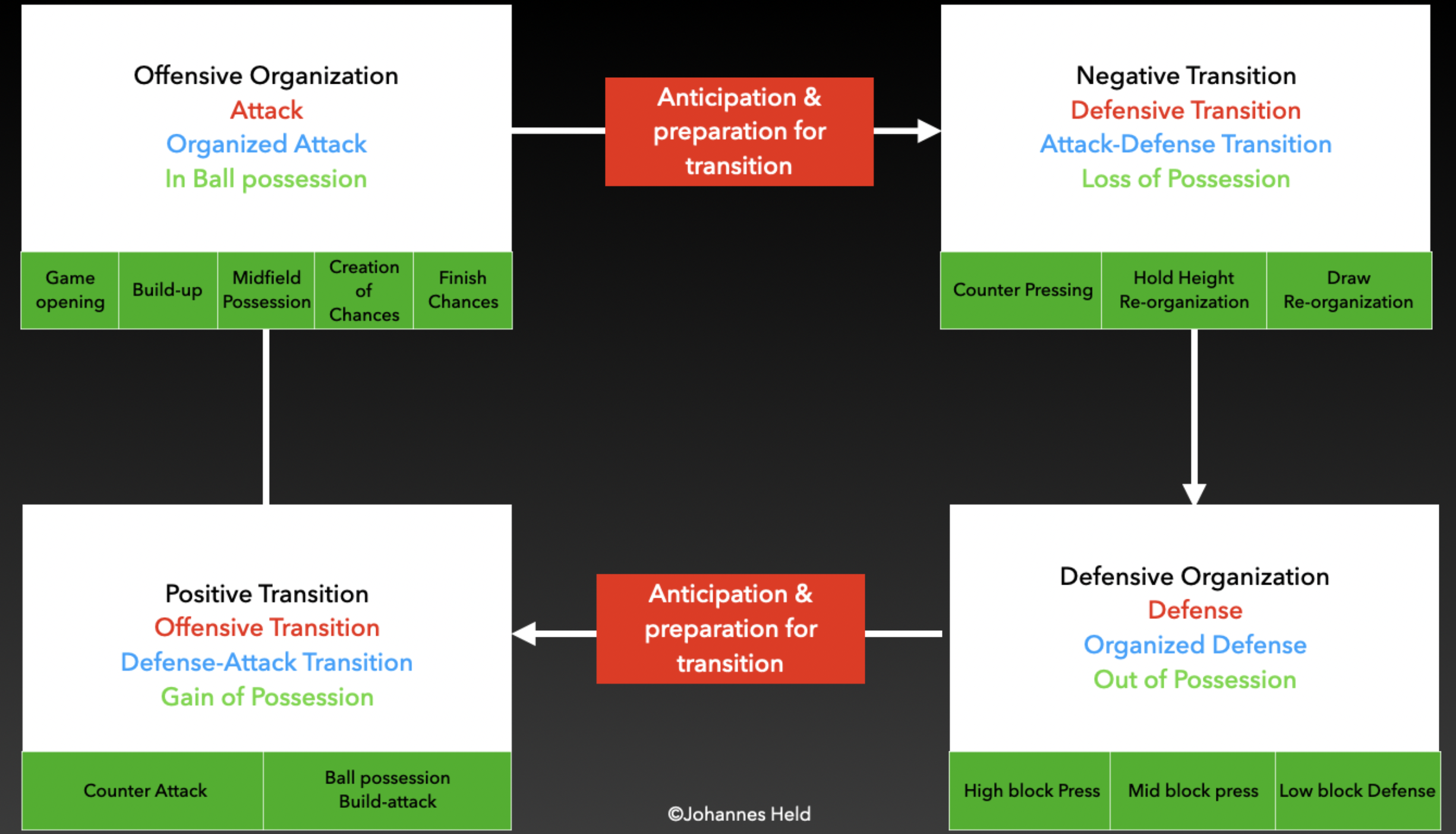

Many coaches understand that the game can be divided into four moments: Offensive Organization, Negative Transition, Defensive Organization, and Positive Transition. It is important to note that the game flows continuously and interchangeably through these phases. Thus, the four moments of the game should not be seen in isolation but as a continuum.

In the illustration below, you can see the four phases of the game, for which I have used different names found in the literature.

Let us add two more more phases to the model. In the illustration below you can see that before a Transition is happening, players have to anticipate and prepare for that transition. Therefore we add these two phases to the model.

Let us add two more more phases to the model. In the illustration below you can see that before a Transition is happening, players have to anticipate and prepare for that transition.

Let us integrate these two moments into our game model.

At this stage, we already know the four main phases of the game, and additionally, we have added two pre-moments before the defensive or offensive transitions. However, the game consists additionally consists of a lot of sub-phases per game phase. Next, we will add sub-phases to each phase of the game. So from now on we will call the four phases as Main-phases and the additional phases we will integrate into the model, we will call them sub-phases.

In my game model, I divide into five sub-phases during the organized attack, three sub-phases during the attack-defense transition, three sub-phases during organized defense, and two sub-phases during the defense-to-attack transition.

First, let's explore the five sub-phases during the organized attack. Normally, possession starts with the goalkeeper, who is responsible for initiating the game. After opening the game (excluding the second ball), the team systematically builds up from the back, progresses play in the midfield (midfield possession), and finally creates chances to score. If the team loses the ball (attack-defense transition), it has three options: to counter-press immediately, to maintain their formation and reorganize, or to fall back as a team, often during the opponent's counter-attacks.

Now, imagine we are in the defending phase, and the opponent has the ball. This can occur at any point in the game, even after a stoppage (e.g., a throw-in or opponent's goalkeeper restarting the game). In this phase, the team also has three overall options: defend using a high, middle, or low block, which indicates the team's defensive line but not the specific pressing strategy (e.g., pressing traps or pressing signals). Another tactic, not mentioned in the graphics, is situational pressing, which often occurs when a team shifts from a midfield press to a high press in response to game context signals.

After defending, when the team regains possession, they must decide whether to counter-attack directly and play deep or to switch to ball possession and rebuild the attack. Now, we understand the four moments of the game, also known as the Main Phases, and the Sub-phases for each Main Phase. However, the model still lacks an important phase of the game: set-pieces.

Set-pieces, which include throw-ins, penalties, free-kicks, and corners, are crucial for team success and must be included in the game cycle model. Normally, offensive set-pieces occur after an attacking phase, and defensive set-pieces follow a defensive phase.

We now have a complete game phase model that includes all phases and sub-phases of the game. However, the game phase model still doesn't dictate how we want to play as a team. It merely defines our phases and sub-phases, which can later be used for periodization to structure our training according to a training focus or for analyzation purpose to have a better understanding of the game.

1.3 The Philosophy of the Club

Working in a professional club or a youth academy necessitates an adherence to a specific philosophy on how they want to develop talented players and the style of play they prefer. I have spent many years as a youth coach at a renowned professional youth academy in Germany, known for its strong emphasis on nurturing young talents. It is essential to acknowledge that a club's philosophy can evolve over time. During my tenure, I observed slight shifts in philosophy, influenced by modern tactical trends in football.

The current philosophy of the club is built around six core values:

Ball-oriented

Creative

Brave

Positionally flexible

Proactive

Offensive

These values serve as the foundational guidelines that coaches should consider when building their game models. For instance, if the primary defensive strategy is to defend in a low block and counter-attack, it clearly contradicts the above values. Thus, these values significantly influence the development of your game model and provide a clear direction.

Take "positionally flexible" as an example. If the goal is to develop players who can adapt to different positions both during and between games, your game model must incorporate this concept. Similarly, considering the "offensive" value, if the team is to embody an offensive style of play, it is crucial to develop players with an offensive mindset. This applies not only during offensive phases but also in defensive situations where, for example, the team might press high to regain possession quickly and transition back to attack.

As you can see from these examples, it is essential to align your game model with the club’s philosophy. If you are not working for a specific club or if you own a club, you have the autonomy to shape these elements yourself. However, the beliefs and principles we hold as coaches will play a significant role in this process, which we will explore in the next section.

1.4 The Desired Playing Style and Beliefs of the Coach

Reflecting on what shapes our beliefs about how a team should play football, most of us can likely recall at least one team that inspired us as coaches. For me, the standout example was Barcelona under Pep Guardiola from 2008 to 2012. In my view, they were the best team in the history of football, and I often wonder how contemporary teams nowadays would fare against them. They inspired me not just with their tiki-taka style, but also with their completeness as a team in every phase of the game. They were a perfect example of a team where the best individuals complemented each other's strengths and weaknesses and played as a unified eleven. Their dominance was not only evident in possession but also after losing the ball. The team's immediate and coordinated counter-press to regain control was striking. Although today we often associate counter-pressing with Jürgen Klopp, a review of Barcelona's games from that era reveals they were exemplary in this tactic.

This example underscores that as coaches, our beliefs about how to play the game are shaped by various experiences. It's not just professional teams that influence our coaching philosophy; our personal playing style also plays a significant role. For instance, I played as a number 10, was creative and technically skilled, but lacked defensive abilities and the attitude for defending. Naturally, it would be unusual for me to advocate for a catenaccio style of football.

Thus, it's clear that both the overarching philosophy and our personal beliefs as coaches will significantly influence the development of our game model. However, perhaps the most crucial factor to consider is the players themselves—their strengths and weaknesses must also guide our approach.

1.5 The Players' Abilities and Individual Requirements per Position

Coaches often hold differing opinions on whether players should adapt to the coach's game model, beliefs, and ideas, or if the game model should be built around the players' abilities. Some coaches prefer flexible players who can fulfill various roles and meet diverse requirements, while others strive to develop a game model that centers on the players' strengths. A third group of coaches seeks a balance, merging the two approaches mentioned above.

However, it's generally indisputable that a game model must consider the players' abilities. In my view, there should be a synergy between the coach's beliefs and ideas and the available talent within the team. I believe a game model needs to be dynamic and continually adjusted to align with the team's capabilities. For instance, if the goal is for the team to maintain extensive ball possession and dominate space and time, the players must possess the requisite skills to meet these demands. Otherwise, players may be placed in roles that do not play to their strengths, potentially leading to ineffective gameplay.

From my perspective, a game model should always be constructed around the players' abilities. If it isn't, the coach risks operating as a "template coach," imposing a rigid framework that players must fit into. This approach might be feasible at the highest levels, where clubs have substantial resources to recruit players that precisely fit their tactical needs. However, in youth teams or clubs with limited financial resources, constant adjustments are necessary to adapt to the available talent.

In summary, a game model must account for players' abilities to varying degrees, depending on the specific circumstances and resources of the team.

Short Summary

We have established that a game model must be derived from the club's philosophy, the coach's beliefs, and the players' abilities—key factors in developing a game model. Therefore, it is crucial for a coach to work for a club that aligns with their vision of how football should be played. It's also worth noting that there are various paths to success in football, but having a well-defined concept is fundamental. Acting spontaneously without a clear game model and a specific plan for how you want your team to play and train might still lead to success. However, it raises the question of whether that success is truly attributable to your coaching or if it stems from other factors, such as merely having the best players.

1.6 Opponent Adjustments

Adjusting strategies based on the opponent is undoubtedly a crucial aspect of game modeling. This involves considering how and to what extent our game should be adapted in response to the opponent's style of play, strategies, tactics, and overall game model.

Personally, I advocate prioritizing the strengths of our own team initially. Only in the second step should adjustments be made to counter specific opponent threats, ensuring that such changes do not diminish our players' natural capabilities. Especially in youth development stages, focusing extensively on the opponent might not be as critical as fostering a strong internal game model. The emphasis on the opponent generally increases as players mature and their competitive environments become more complex.

For instance, consider Player A, who excels as a central midfielder where he can utilize 95% of his strengths, but also has the capability to play as a right fullback, albeit at 75% efficiency. If a coach positions him as a right fullback solely based on tactical needs against a particular opponent, it might inadvertently weaken the team's overall performance.

Therefore, it is essential during youth development for players to experience various positions. This not only promotes flexibility and adaptability to the evolving demands of the game but also deepens their understanding of the game from multiple positional perspectives.

In summary, while the game model must be adaptable to opponents, the extent of these adjustments is subjective and largely depends on the coach's strategy and the developmental stage of the players. As players age, the significance of opponent adjustments tends to increase.

1.7 Development or Success Approach

A frequently debated topic is whether good results are indicative of effective player development. The answer to this question is not straightforward. Let’s consider some examples to explain why success on the field does not always equate to optimal player development.

I recall a few players I trained in the past who were highly successful in their age groups but struggled as they matured, eventually becoming unable to meet the academy's standards. Despite winning nearly 90% of their games against some of Germany's top academies and being key players, these individuals were later released from the club. One player, in particular, was dismissed because he was deemed too slow, despite having consistently played as a central midfielder. From a developmental standpoint, this was suboptimal. Each position on the field demands varying skills across technical, tactical, athletic, psychological, sociological, and cognitive areas. Young players benefit from experiencing these varied demands, gaining new stimuli essential for comprehensive development. Playing the same position continuously can limit these developmental stimuli, potentially stunting a player's growth in a high-performance environment.

This brings us to why some coaches prioritize immediate success over long-term player development:

- The coach values short-term success over comprehensive development.

- The coach faces pressure from the club's management or other stakeholders.

- The coach believes that winning is a proxy for optimal player development.

It's crucial to specify the context—while professional football often emphasizes winning, many clubs also expect coaches to develop young talents within the first team, allowing them time to adapt to professional levels. However, in developmental settings, an overemphasis on success can hinder growth. There’s a saying that you learn more from failure than from success, and there is truth to this, particularly in sports.

Why is this relevant to our discussion on game models? Because a game model should accommodate these developmental needs. For instance, if we prioritize ball dominance, our game model should facilitate extensive ball contact, shaping our tactical principles around possession and ball-handling skills. Conversely, a model focused on counter-attacks might lead to a different developmental trajectory, where players spend less time in possession and more on quick transitions, possibly at the expense of technical skill development.

Additionally, consider goal kicks: if a goalkeeper's first choice is to play long balls, players miss out on learning how to build up from the back, progressing the attack through various phases.

All these considerations are pivotal when developing a game model. As we've discussed the game's four phases and set pieces, along with influential factors in game model development, the next chapter will delve into how to actually construct a game model for our team.

Free E-Book

Jane Doe

Johannes Held is an A-License Football coach who worked for the youth department as a youth coach of a German 1st Bundesliga club. He worked in several countries, with different age groups and all kinds of levels. During his time working in the Bundesliga club academy he coached players like Rocco Reitz (VfL Borussia Mönchengladbach, Malick Thiaw (AC Milan) or Armel Bella (FC Southhampton).

Popular posts

The Development of a Game Model Part 1

April 22, 2024

The Development of a Game Model Part 2

April 22, 2024

The Blueprint to a Successful Soccer Training Session

April 22, 2024

25 passing drills for your team

April 22, 2024

April 26, 2024

About this blog

I'm Johannes Held, a UEFA A-licensed coach dedicated to helping football coaches design impactful training sessions. With a background in sports science and marketing, I've worked with talented players like Rocco Reitz (Borussia Mönchengladbach) and Malick Thiaw (AC Milan) during their formative years. My experience ranges from coaching in top youth academies in Germany to developing ambitious football projects in China.

Created with ©systeme.io