How to develop a game model? Part 2

In the first part of "How to develop a game model" we delivered general thoughts and ideas, before actually developing our game model. Today we will step by step in discover how we can actually develop our game model from scratch.

When it comes to developing a game model, the following steps should be undertaken:

1. Identify the Desired Style of Play: What style do I want my team to adopt?

2. Recognize Unwanted Play Styles: What styles of play do I want to avoid?

3. Determine Game Requirements: What are the specific requirements of my desired style of play?

4. Conduct an Ist-Analysis: Analyze the current team—what types of players are present, and what types of players do I aim to develop?

5. Select Appropriate Game Systems: Choose suitable game systems at the macro-level and define positional requirements at the micro-level.

6. Define Meso-level Requirements: Outline intermediate requirements that bridge macro strategies and micro tactics.

7. Establish Values for each Main-phase: Determine the core values that will guide the team's overall strategy for each Main-phase.

8. Define Principles for Each Phase of the Game: Establish guidelines for each distinct phase of gameplay.

9. Define Principles for Each Sub-phase of the Game: Detail the specific guidelines for each sub-phase within the larger phases.

OK let us begin.

Step 1: Identify the Desired Style of Play: How do I want my team to play?

To begin defining your desired style of play, I recommend starting with brainstorming or creating a mind map. This process should focus on identifying the key elements that encapsulate what you want your game to represent. Aim for a broad characterization rather than delving into excessive detail initially.

Step 2: Recognize Unwanted Play Styles: How do I not want to play?

As illustrated previously, the way I want my team to play has been outlined. To further refine the conceptual idea of your game model, it's beneficial in a subsequent step to define how you do not want to play. This approach helps in setting clear boundaries and focuses for your game strategy.

Step 3: What are the requirements across the six areas for my desired style of play?

We have now differentiated between how we want our team to play and how we do not want to play. This distinction provides us with a clear conceptual foundation for our game model. The next step is to define the specific requirements of our game across all six areas, aligning them with our conceptual ideas. Below you can see an example.

After completing this step, we will have a clear understanding of the requirements needed to develop the game model across the technical, tactical, physical, psychological, sociological, and cognitive levels. These requirements are illustrated in the image above. The next step is to compare the requirements specified for our game model with the existing characteristics of the team.

Step 4: Conduct an Ist-Analysis: Analyze the current team—what types of players are present, and what types of players do I aim to develop?

At this stage, you need to ensure that the desired style of play you initially defined (the conceptual idea of the game model) and the requirements of this game model are compatible with the existing structure of the team.

As a coach, you must evaluate whether the conceptual idea of your game model can be realistically executed by your players, both individually and collectively. If not, it is essential to consider whether the players could adapt to this style in the future. This consideration is particularly pertinent in professional football, where there is limited time to develop a completely new game model. In such settings, a coach must often adapt to the existing structures of the club. However, in youth coaching, a game model can also serve as a developmental goal, aiming to cultivate this style of play and its associated requirements over time. Therefore, even if your team currently lacks the necessary characteristics, these are the attributes you aim to develop.

Once this step is complete, you can either decide to adjust your game model based on these findings or proceed to design your game model. I personally prefer to start by defining the game systems and the requirements for different positions.

Step 5: Select Appropriate Game Systems: Choose suitable game systems at the macro-level and define positional requirements at the micro-level.

One of the most debated topics among coaches is which system to use for their team. Opinions vary:

- Some coaches believe their team should be able to play different systems, adapting to various game situations.

- Others focus on mastering one specific system thoroughly.

- Some prefer to switch formations during different phases of the game, such as attack and defense.

- Others adjust their formation in response to the opponent’s tactics.

Historically, each approach has had its successes, but modern football commonly demands that teams exhibit tactical flexibility. This often means playing different systems not only from one match to another but also within a single game. A frequent strategy seen in recent years involves central midfielders dropping between the central defenders to form a dynamic back three. This adjustment allows full backs to take higher positions and wingers to operate in the half spaces, enhancing both defensive stability and offensive reach.

Similar strategies are also employed defensively. Many of the world's renowned coaches advocate for mirroring the opponent's system when playing against the ball. This involves aligning the defensive team’s formation to directly counter the opponent's setup. For instance, if the opponent fields a formation with a 'six' (defensive midfielder) and two 'tens' (attacking midfielders), the defending team might counter the 'six' with a 'ten' and each 'ten' with two 'sixes'. This tactic is illustrated in example 3. In example 4, you will find a variant where the defensive team completely mirrors the opponent’s formation, with the objective of ensuring man-to-man markings across the entire field. By mirroring the formation, each defender is automatically assigned an opponent.

All in all, the effectiveness of a defensive strategy heavily depends on the chosen formation and how the opponent interprets their own formation. In Germany, there is a common caution that the formation alone does not reveal how the opponent will play their game. It merely specifies the locations of the players on the pitch at a particular moment. Thus, formations should be viewed dynamically, as they can change according to different moments of the game. What’s crucial is how the opponent interprets their formation, often referred to in Germany as the "system of play."

Having introduced sufficient theory, we can now begin to select our game model's formation to create a system of play. As a coach, it’s important to decide which approach to adopt. Personally, I prefer to have one main formation while allowing my team to switch formations based on the phase of the game, sub-phase, and the opponent’s formation.

I choose to develop my team in a 4-3-3 formation because I believe it nurtures all the positions required in modern football. This formation also provides multiple lines, aligning with one of my key principles during attack—to maintain at least four lines—and facilitates easy transitions into other formations.

You can observe good triangulation, which is illustrated in the image below. It’s important to note that while the formation may appear static, the system of play represents the dynamic interpretation of that formation.

We have now decided on the formation and the overall strategy to allow fluid changes between formations during different phases and sub-phases of play. The next step involves defining the position-specific requirements for each player.

To be thoroughly precise about the requirements of your positions, you should develop a model that encompasses all four phases of the game, including at least the sub-phases. I will illustrate this by focusing on one position to define the requirements for each phase and sub-phase of the game.

In Table One on the next page, you can see the requirements for a Position 6 (P6) across all phases and sub-phases of the game. It's important to note that these requirements are primarily described from tactical and technical perspectives. While it would be possible to supplement the table with other factors such as physical, psychological, and socio-affective elements, I believe that for the purpose of developing the game model, it is not necessary to overemphasize these aspects. One aspect not covered in this table is the positional requirements for set-pieces, which you can add as needed.

6. Define Meso-level Requirements: Outline intermediate requirements that bridge macro strategies and micro tactics.

In the previous section, we discussed the individual requirements of positions within the system, using Position Six (P6) as an example. We touched on what is meant by Mesolevel requirements but did not explore it in detail. Mesolevel requirements pertain to the behaviors of a group of players within the team. According to the model of tactical periodization, we can distinguish among intersectorial, sectorial, and group sectors.

To simplify, let's start with the sectors. In a 4-3-3 formation, for example, there are three distinct sectors: the defensive line, the midfield trio, and the attacking line. The term "intersectorial" refers to the connections between different sectors, such as the interaction between the number six and the two central defenders, or between P10 and P8 with the attacking line. When we talk about a group, we are referring to a smaller subset of players, such as two strikers, or a winger and a fullback.

Finally, the individual scale corresponds to the Micro-level, focusing on one specific position, while the Macro-level encompasses the entire team. The differentiation between these scales is visible in the image above. In Germany, we typically categorize tactics into Individual, Group, and Team tactics. Additionally, some coaches include Partner tactics, which examine the behavior of two interacting players. Essentially, the model of tactical periodization shares many similarities with the German approach.

It is crucial to distinguish between these scales or levels because they significantly impact the training model, periodization, and the analysis of both your team and opponents.

To provide a comprehensive understanding without delving too deeply into complexities, it’s important that your game model also considers player behavior on the Meso-level. Next, I will offer some examples for each of these scales.

Group-Sector Examples:

- Two pivots

- Two central defenders

- Left fullback paired with left winger

- Two strikers

- One striker paired with P10 (advanced playmaker)

- Other combinations as applicable

Sectorial Examples

- Defending Line:

- Back four - Back three

- Midfield Line/Sector:

- Encompasses all midfielders as a unit

- Attacking Line/Sector:

- Includes all forwards and attacking players

Inter-sectorial Examples:

- P6 (defensive midfielder) and the entire defending line

- Two pivots combined with the defending line

- Midfield line integrated with the defending line

- Combinations involving a winger, central midfielder, striker, and fullback

A common approach to utilizing these scales involves segmenting specific areas of the field to focus on the behavior of particular sectors. For instance, if a coach wants to train the inter-sectorial interactions between a winger, fullback, P8/P10 (midfielders), and a striker during an attacking phase along the wing, they would isolate the relevant area of the field. This allows the coach to tailor the training exercise specifically for that segment, enhancing the effectiveness of the drill. An example of such a training setup can be seen in Training Form 1 below. This method is versatile and can be effectively used to train both individual (micro-level) and team-wide (macro-level) behaviors.

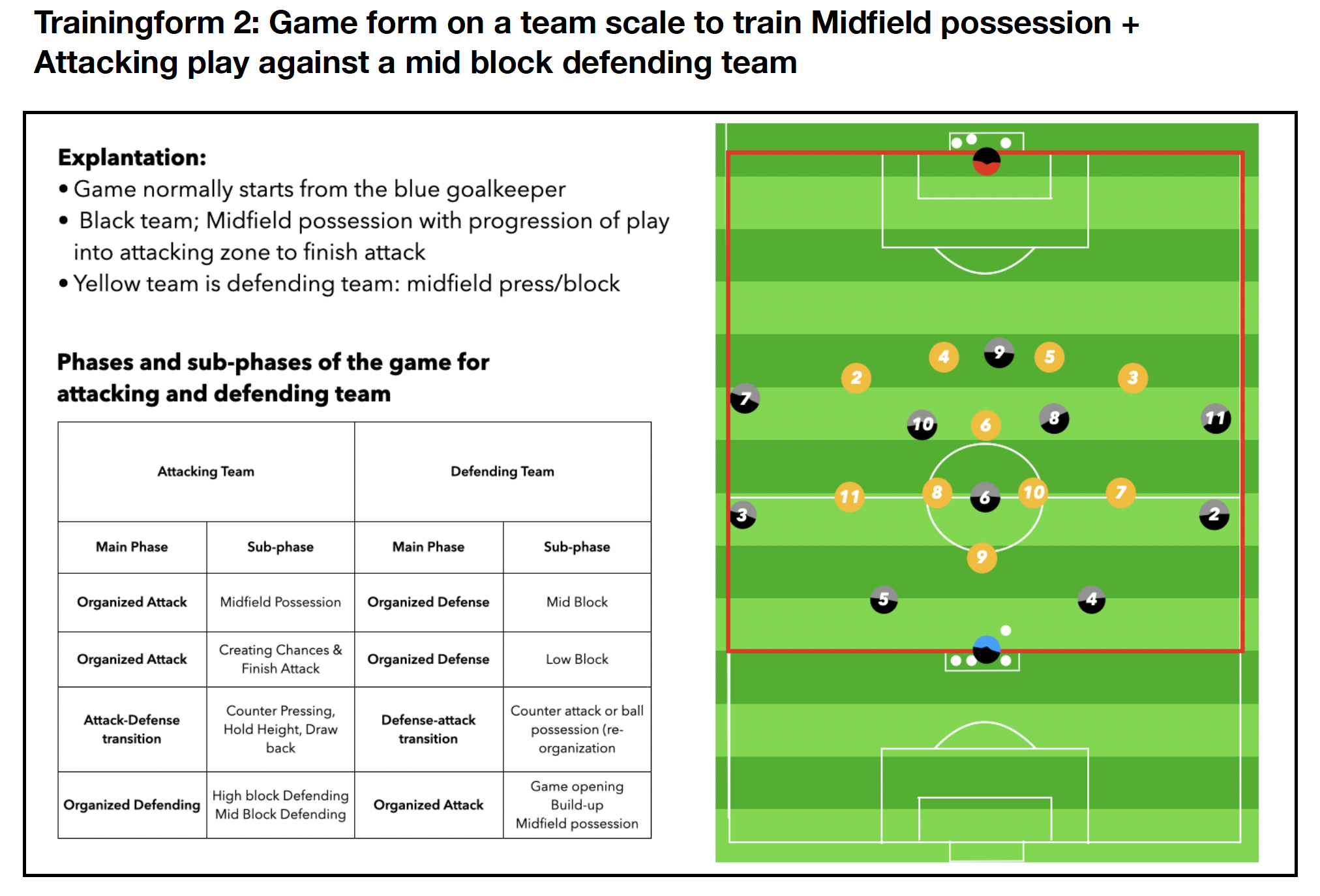

This method can be applied effectively at both the micro and macro scales. Training forms 2 and 3 provide examples of how this approach is implemented for each scale respectively.

Training Form 2 demonstrates how to develop a training session based on the introduced model. This form is considerably more complex than Training Form 1, as it involves more players and incorporates various phases and sub-phases of the game. This highlights an important principle: the complexity of a training session increases with the number of players and the range of game phases involved. This is why it's crucial during training to engage with all three levels (micro, meso, and macro).

Training Form 3 illustrates how to create a training session on the micro-level, rooted in real-game scenarios. It's important to note that this form still includes different phases and sub-phases of the game. I want to emphasize that isolating a specific moment of the game is possible, but in my opinion, it may not fully represent the continuous flow of the game through its various phases. For example, if we train frontal offensive 1 vs 1 over the wing and decide to end the exercise immediately after a loss of possession, this would be incomplete. In an actual game, after losing possession, the scenario would naturally transition into attack-defense for the attacker and defense-attack for the defender. Therefore, the training form should include these transitions to better simulate game reality.

Unfortunately, I often see coaches isolating specific moments without considering the game's dynamic flow. This is a crucial consideration for coaches when planning and executing training sessions. While it is possible to focus on specific details by isolating an action, it is also essential to consider how the game could continue after a change of possession.

Ideally, each training session should incorporate at least one follow-up action in a transition moment to mimic the game more closely. Continuous training forms are generally more reflective of game reality because they include teammates, opponents, time pressure, spatial constraints, and opponent pressure. In contrast, unopposed practice might be simpler for players to understand and execute due to the absence of direct pressure, but it is less representative of actual game conditions.

Training drills that are unopposed are still valuable for introducing concepts or as a methodological step from unopposed to opposed drills and eventually to game-like scenarios.

We have now discussed the importance of understanding and utilizing all three levels—micro, meso, and macro—as well as the five scales identified in the method of tactical periodization. I have also provided an introduction on how to design training forms based on these scales. We will revisit this discussion when we begin to talk about the training model.

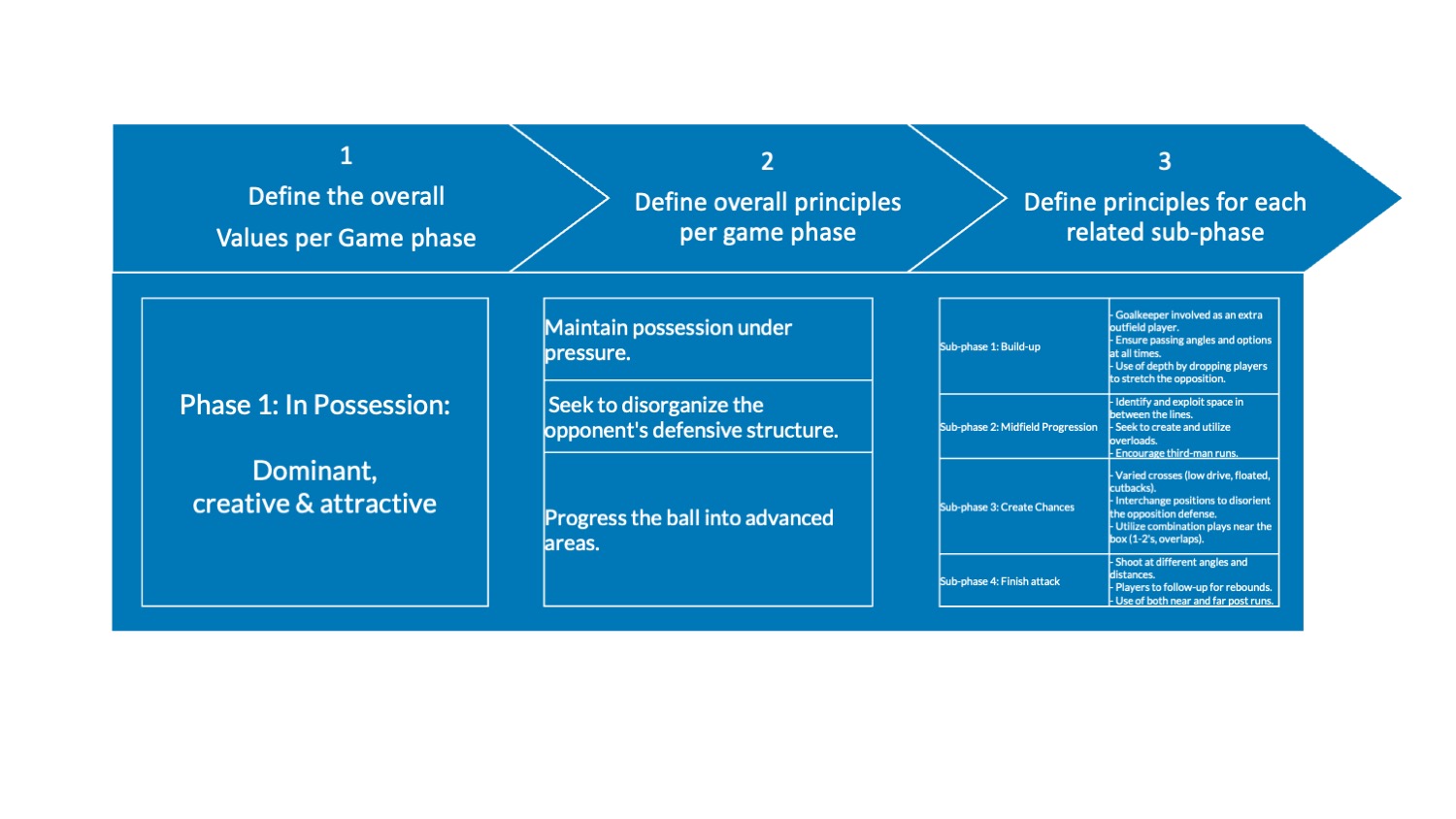

7. Establish Values for each Main-phase: Determine the core values that will guide the team's overall strategy for each Main-phase.

Start by determining the core values that encapsulate the team's ethos for each Main Phase of the game. For example, the values selected, such as Dominant, Creative, and Attractive, will guide the overall strategy and define the character of play.

8. Define Principles for Each Phase of the Game: Establish guidelines for each distinct phase of gameplay.

With the values in mind, establish principles that translate these values into tangible guidelines for each phase of gameplay. This ensures that the team’s play is consistent with the established values.

9. Define Principles for Each Sub-phase of the Game: Detail the specific guidelines for each sub-phase within the larger phases.

Further detail is required for each sub-phase, creating specific principles of play that align with both the overarching values and the strategic needs of each sub-phase.

This article has outlined a comprehensive approach to developing a game model for football teams. From the initial determination of the desired style of play to the detailed articulation of individual game phases, we have followed a step-by-step methodology that allows coaches to craft a clear and coherent strategy.

We began by identifying the preferred playing style and acknowledging which approaches we aim to avoid to ensure the chosen style remains uncompromised. We then detailed the specific requirements that come with our desired way of play, followed by a thorough current state analysis of the team to understand both the present player roster and the future development needs.

Next, we selected appropriate game systems at the macro-level and defined positional requirements at the micro-level. We bridged these with meso-level requirements, ensuring connectivity and flow within our tactical approach. Core values were established for each main phase of the game, guiding the overall team strategy. Then, principles were established for each game phase and further detailed for each sub-phase.

Through this structured approach, coaches can ensure that every element of the game model—from the macro to the micro-level—is carefully considered, allowing for precise implementation in training and matches. In closing, we emphasize the importance of flexibility and adaptability within the game model to respond to the dynamic nature of football and the specific challenges that arise from team composition and competitive circumstances. I hope this article has been informative and has provided valuable insights into the art of football coaching.

Free E-Book:

Johannes Held

Johannes Held is an A-License Football coach who worked for the youth department as a youth coach of a German 1st Bundesliga club. He worked in several countries, with different age groups and all kinds of levels. During his time working in the Bundesliga club academy he coached players like Rocco Reitz (VfL Borussia Mönchengladbach, Malick Thiaw (AC Milan) or Armel Bella (FC Southhampton).

Popular posts

The Development of a Game Model Part 1

April 22, 2024

The Development of a Game Model Part 2

April 22, 2024

The Blueprint to a Successful Soccer Training Session

April 22, 2024

25 passing drills for your team

April 22, 2024

April 26, 2024

About this blog

I'm Johannes Held, a UEFA A-licensed coach dedicated to helping football coaches design impactful training sessions. With a background in sports science and marketing, I've worked with talented players like Rocco Reitz (Borussia Mönchengladbach) and Malick Thiaw (AC Milan) during their formative years. My experience ranges from coaching in top youth academies in Germany to developing ambitious football projects in China.

Created with ©systeme.io